Fuksas Building Update by Massimiliano & Doriana Fuksas

Actar, 2015

Hardcover, 250 pages

First off, I should admit that I don't have nor haven't seen the first

Fuksas Building, published by Actar in 2011, which this book updates. So I can't really comment on how well this book extends the content of that monograph, nor if it is worth having in addition to that book. Second, I should admit that I have a love-hate relationship with Fuksas's work, which I have seen little of in person (the

Armani Fifth Avenue springs to mind), but which, like other architects these days, has some interesting qualities at a small scale that don't necessarily work when blown up larger. The glass roof funnels of the

New Milan Trade Fair, for example, are appealing (if a repeated element for Fuksas), but not at what looks to be a half-mile length of the concourse. The buildings of Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas are increasingly larger (heck, they just finished

an airport in China), but I'm not sure their architecture responds accordingly. Nevertheless, I like the brevity of the spread before the first chapter, Buildings, which is found in lieu of a traditional, multi-page introduction:

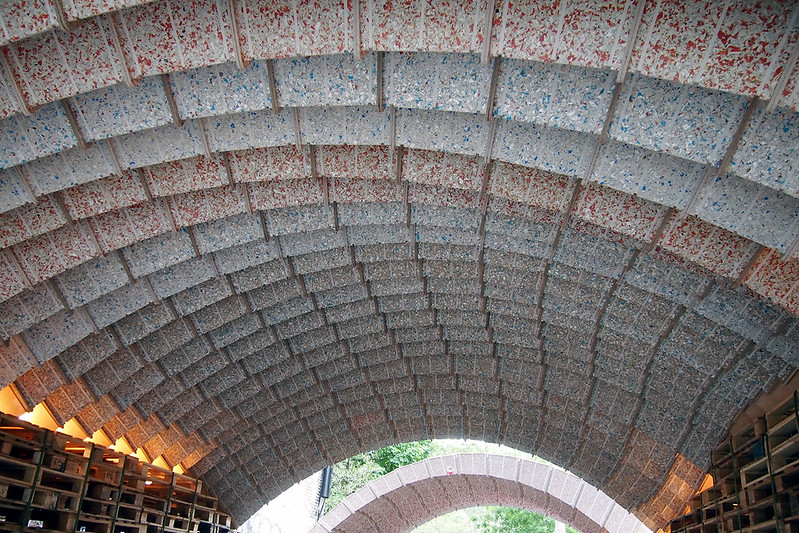

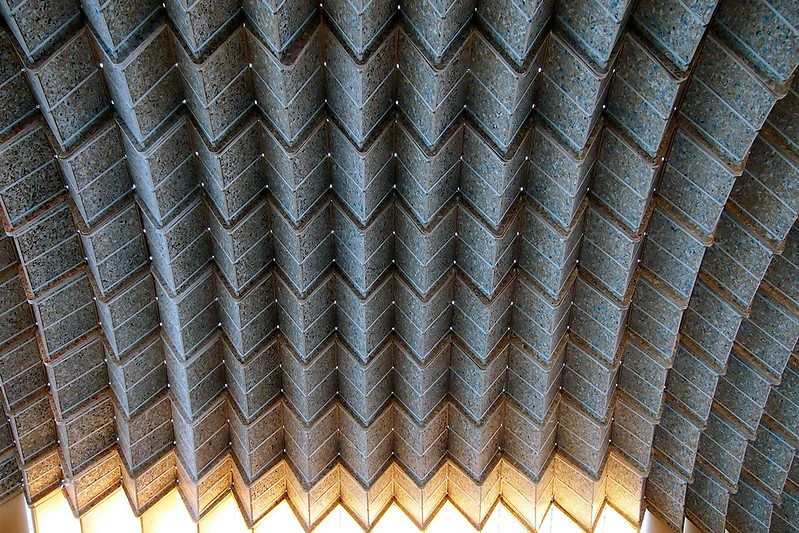

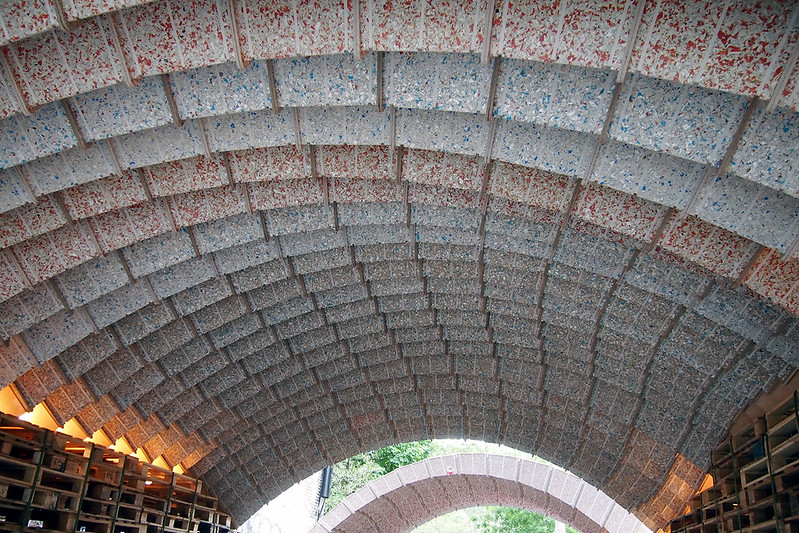

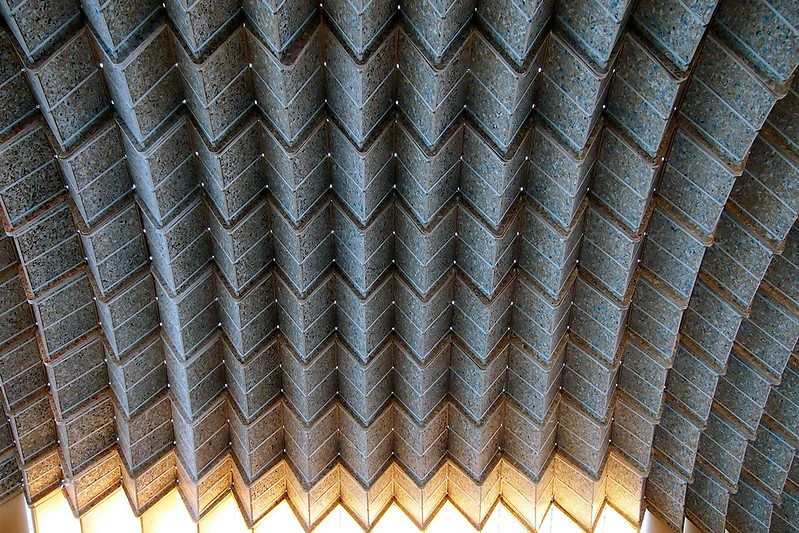

This statement made me wonder if in fact they don't have a style. At first I agreed, since the three projects mentioned and linked above are a pretty diverse bunch. Regardless, they are recognizable as Fuksas projects, along the lines of Renzo Piano's buildings being recognizable as his own even though he doesn't have a signature style in the vein of, say, Richard Meier, to cite the most obvious example. Like Piano, Fuksas's buildings have a "style" at the level of detail, element and surface: undulating glass roofs, blobs with perforated surfaces, and cantilevered glass boxes, to name a few. Also, the husband-wife duo really like to juxtapose hard-edge boxes with soft forms and surfaces, such as inside the Armani Fifth Avenue and in the New Rome-Eur Convention Centre and Hotel, which is highlighted in the Construction chapter:

The other chapters in the book, in addition to Construction, which only has the one project, are: Building, with eight buildings, most of them completed in 2012 and 2013, and documented through photographs and brief text; Project, which has five projects briefly explained through renderings; and Drawing and Detail, which has construction documents (plans, sections, details, etc.) for nine projects, seven of them from the Building chapter. Drawing and Detail is easily the most valuable part of the book for architects, since it includes the types of drawings and information that are otherwise overlooked in monographs. It's great to see, for example, sections through the "blob" inside the boxy EUR project, even if the individual sections are at a small scale (below). Since the drawings reference the built work at the front of the book, other architects can grasp how the projects moved from drawing to building, one thing that makes this book an appealing one, especially for fans of Fuksas's style-free architecture.