SCI-Arc Press, 2014

Paperback, 144 pages

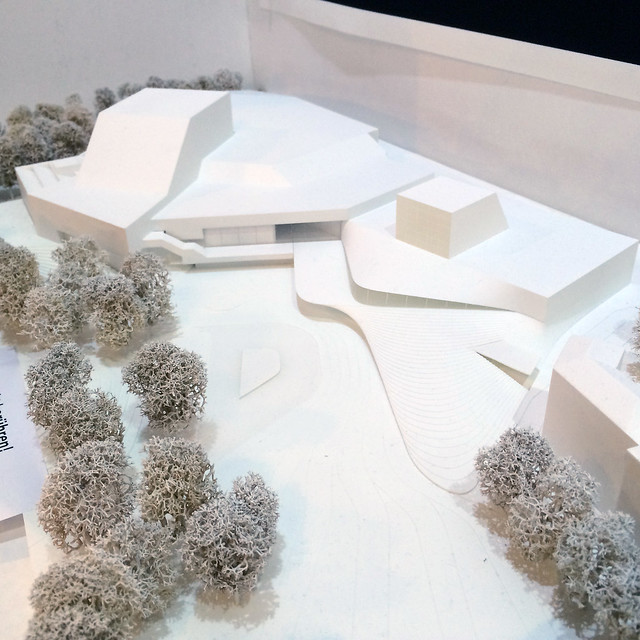

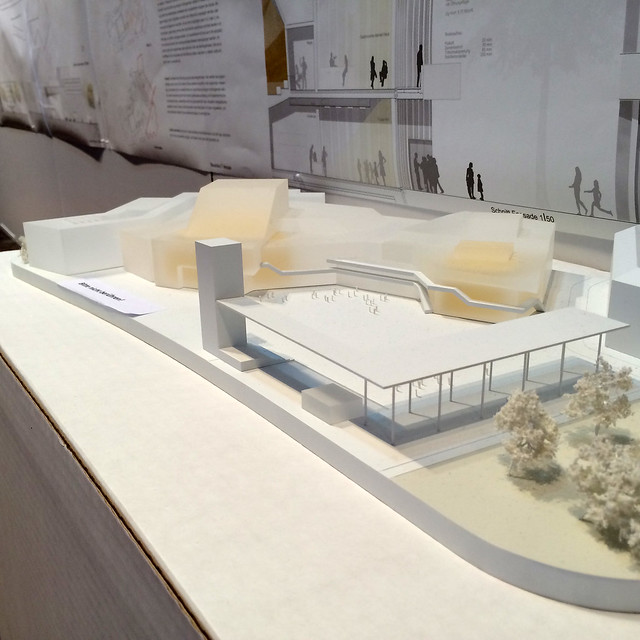

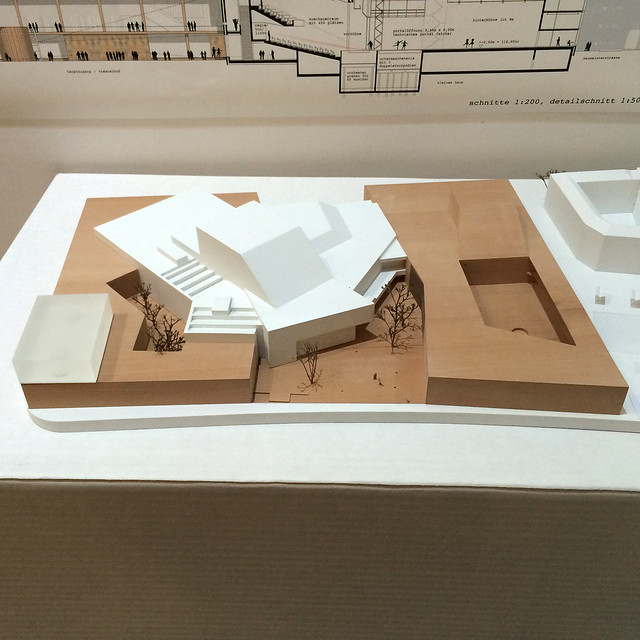

This book presents three pavilions designed by Oyler Wu Collaborative for SCI-Arc, where husband-and-wife partners Dwayne Oyler and Jenny Wu teach. This situation is certainly a unique one, since the school has acted as client for the duo's design proposals not once, but on three consecutive occasions, from 2011 to 2013. They were asked each year to create a shelter for about 900 people for the graduation ceremonies taking place in the school's parking lot each September. The first pavilion was dubbed Netscape, an appropriate name given the 45,000 linear feet of knitted rope strung between the tube-steel trusses. Netscape survived into the following year, so Oyler Wu were given the opportunity to add a stage structure, in effect improving the experience of the ceremony while exploring more means of design and construction in the smaller project. Stormcloud, the 2013 pavilion celebrating SCI-Arc's 40th anniversary, reused the Netscape structure, but for various reasons the architects opted for fabric rather than rope, giving the pavilion a much different character than the previous iteration.

[SCI-Arc Graduation Pavilion by Oyler Wu Collaborative, 2011]

Yet even as the book does an excellent job of documenting these three SCI-Arc pavilions through drawings, models, construction photos and the words of Oyler and Wu, the reader does not confront them until page 70, at the halfway point of the book. Preceding the "trilogy" are comments from fellow SCI-Arc faculty: Dora Epstein Jones puts down some dense theoretical prose to situate the duo's work in a historical context; soon-to-be Director Hernan Diaz Alonso sees Oyler Wu's work in relation to his own primarily unbuilt designs; and John Enright grasps the learning process embedded in the prototype designs of the three pavilions. Following those introductory remarks is a transcribed lecture of Oyler and Wu speaking at SCI-Arc in January 2013. The lecture is similar to one I attended in 2012 in which the couple explained clearly how lessons learned from one project – be it in design and/or realization, the latter often by themselves – were carried over into another, much as they were in the three SCI-Arc pavilions.

[Sketch by Dwayne Oyler]

"Lineworks" is the name of the January 2013 lecture, and it is an appropriate title, given that lines define much of what they have designed and built to date. They can be found in pieces as early as Oyler's undergraduate projects, which I was privy to as a classmate in undergraduae architecture school, but it's his ongoing sketchbooks full of pages of layered and knotted lines that are most extraordinary. A carryover from Oyler's experience working with Lebbeus Woods (check out Woods's sketchbook pages to see the similarity), the 15 years worth of drawings display an increasing complexity and sureness of hand in creating what he refers to as "spatial fields." The spaces depicted are thick, dense with lines that interact with each other to create even thicker lines and nodes of hierarchy. Even as these spatial fields defy realization, it's pretty easy to see the relationship between these drawings and projects like Screenplay and The Cube.

[Stormcloud installation at SCI-Arc, 2013]

Publication of this little book (about the same size but a bit longer than their previous book, Pendulum Plane) coincides not only with the completion of the three SCI-Arc pavilions, but also with some new directions for the collaborative. Most notably, their design for a 16-story residential building in Taipei is now under construction (on the site of the Sales Center they built for it), their Screenplay installation created for Dwell on Design in 2012 was recently added to the SFMOMA permanent collection, and Jenny Wu launched LACE, a line of 3D printed jewelry, mainly rings and necklaces. Even as Oyler and Wu are venturing into larger and more diverse realms and being recognized for their work, their root explorations remain. Just look at LACE, which utilizes 3D printing technology and therefore could be just about anything, could take any form. But the duo's "linework" remains, evidently serving as a means of making decisions about form and creating things that are downright appealing.

.jpg)

[LACE by Jenny Wu, Catena Necklace]